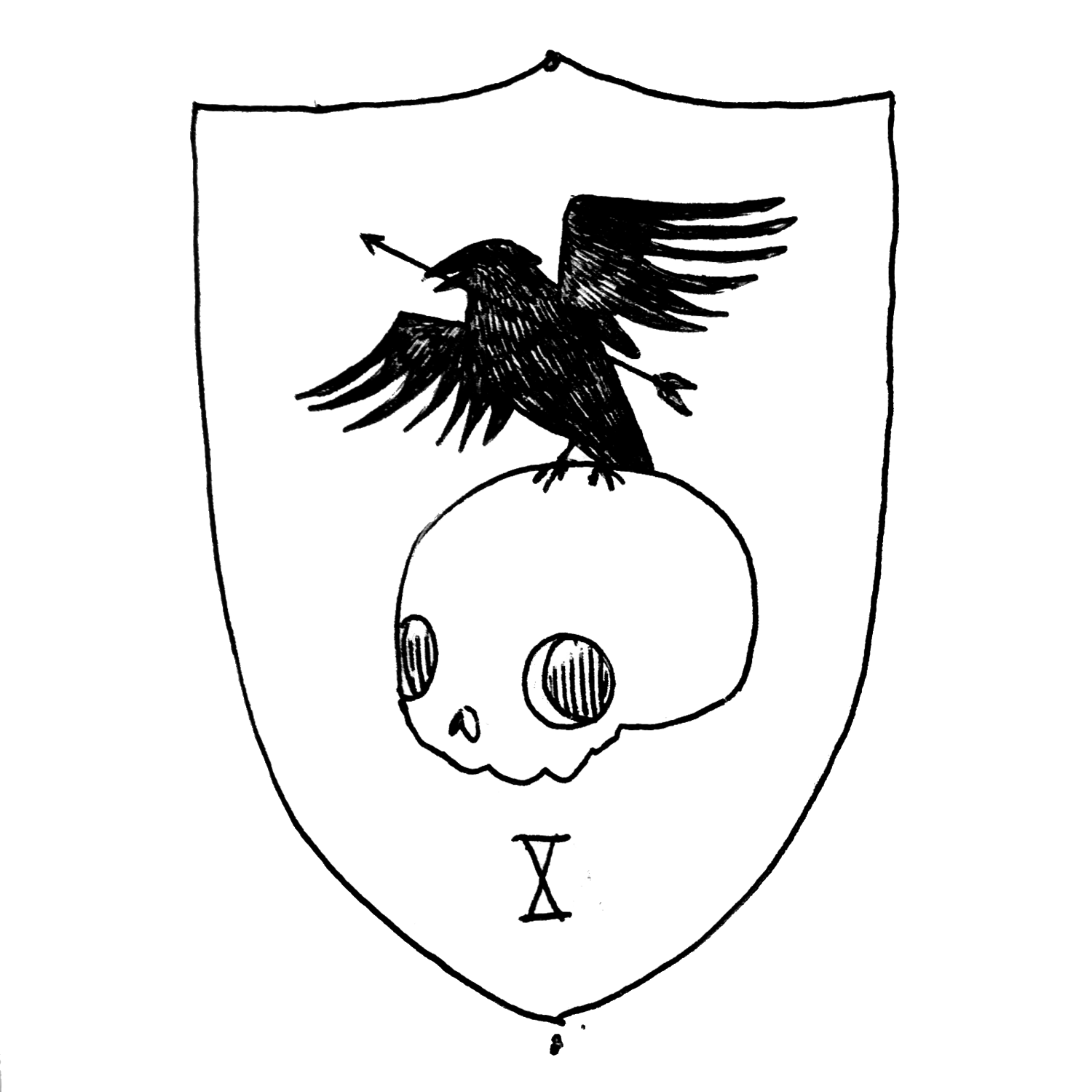

Design Notes V: Going Rogue and GLOGing the Thief

Thief. Rogue. Specialist. This class has a million names. I prefer the term “rogue” even if that bucks the original naming scheme of “thief”.

This is a tough one to tackle. The thief has the original “skills” in D&D, like being able to climb sheer surfaces and hide in shadows. If I remember my D&D history correctly, the introduction of the thief caused problems because it delineated what other classes couldn’t do. If the thief is the only one that can “hide in shadows” and has a 10% chance of success at first level, that means your fighter isn’t going to pass muster. Like, ever.

By 5th edition, Rogues are the most skilled of all classes. get double their proficiency to some skills at first level, which gives them a 70 to 90% success rate against basic difficulties. That also means that your Rogue can be more skilled in anything than anyone else. Better in arcana than the wizard and, if they choose, better in medicine than the cleric.

For me, it just… feels weird? It isn’t what I want from the class. But we have to be able to capture the deftness of the rogue without shutting out everyone else. I don’t want any of the other classes to feel like they can’t try to sneak.

Now that I am done complaining, let’s figure out what rogues do so we can compress it down into 4 templates.

What can rogues do

Right from the beginning, rogues know how to be quiet and do some thieving better than anyone else. They move silently, hide in shadows, pick pockets, and they know how to get into buildings (through the second story, no less). Sure, other classes could be stealthy, but our Rogues are classy about it.

Second, rogues perceive stuff. They find traps, secret doors, and even hidden enemies. In short, they know what’s going on before the rest of the party does.

Third, Rogues do damage. If they hit a target that isn’t paying attention, they get their backstab damage. There has been some variant of this in every version of D&D: Backstab goes all the way back to the 1st edition days and has been an integral part of class since the ‘70s.

So, there are three things we have to hit: Thieving, perception, and damage.

Let’s make our rogue then.

I really want a game without defined skill checks, so the 5e method of giving double proficiency doesn’t sit right with me. I am going to steal some ideas from better designers. If you open up your copy of Freebooters on the Frontier, their Rogue has their own power called cunning. You gain cunning based on your intelligence modifier and the number of rogue templates you have. I love the idea that intelligence drives the rogues’ powers. Rogues succeed because they are planners and thinkers, not because they are merely quicker than their adversaries.

At the first template, you can spend your cunning on automatic success for climbing, hide in shadows, moving silently, picking pockets, and the occasional sneak attack as long as there is a chance for success. Done. These are all classic “skills” for thieves from 1st edition. However, what sets our rogue apart from the other classes is perfect planning: they don’t have to roll or rely on a check to succeed. The fighter is, of course, still welcome to try…

This might be too powerful, but remember the beginning character likely has 2 or 3 points of cunning and cunning only recharges on a short rest. Our rogues won’t be using these powers too often.

For the 2nd template, I wanted to cover perception. I added the questions from the Discern Realities move from Dungeon World. In short, a player can spend a cunning point to force the DM to answer one of the following questions:

What happened here recently?

What is about to happen?

What should I be on the lookout for?

What here is useful or valuable to me?

Who’s really in control here?

What here is not what it appears to be?

I really like using the questions from Discern Realities for two reasons. First, these questions show higher-order reasoning that exemplifies rogues. It isn’t about the trap you find, per se, it is about why the trap is there and who set it up (it is, of course, easy to ask these questions while the fighter is taking the brunt of the damage). Secondly, the questions from Discern Realities drive the action forward. Although the DM can respond to these questions with a negative “Nothing is about to happen”, in general, these questions are designed for DM to give the players information to keep the game flowing.

For the 3rd template, the rogue really comes into their own with an improved sneak attack. Add (+2d6 damage) for the cost of one cunning.

For the 4th template, the rogue becomes the master of their domain. They can spend two cunning to reroll a d20, and they get double cunning points. Again, this might be too powerful, but I really like the idea of the Rogue being so quick-witted to change reality.

This has been a complete redesign of the thief/rogue and doesn’t really follow any other GLOG design convention out there. I am sure, after playtesting, there will be changes to the class but for now, get your copy here.

Interested in more design work? See my notes on the Fighter, Cleric, and Wizard.